Philip Roth...Everyman

April 25, 2006 (The New York Times)

April 25, 2006 (The New York Times)PHILIP ROTH, HAUNTED BY ILLNESS, FEELS FINE

By CHARLES McGRATH

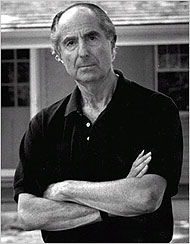

Philip Roth, now 73, is in excellent health. He had back surgery a year ago but is fully recovered. He exercises faithfully, avoids red meat and consumes a morning ration of Great Grains cereal. Proof of his fitness is the jacket photo for his new novel, "Everyman," which is being published by Houghton Mifflin. This is the first time in ages that Mr. Roth, famously private and publicity-averse, has allowed his likeness to appear on one of his books.

The reason for Mr. Roth's pre-emptive photographic strike is that "Everyman" is a book about mortality. It begins in a graveyard and ends on the operating table. And Mr. Roth is hoping that the pictorial evidence on the book's jacket will stave off autobiographical interpretations. "I figure this will halve the number of phone calls from kind friends saying, 'I didn't know you were so sick,' " he said recently.

"Everyman" is a slender volume of less than 200 pages. In that brief span, the novel's nameless protagonist, a retired advertising man, undergoes a series of increasingly drastic surgical procedures. Stents, angioplasties, operations to ream out his carotids and one to install an interior defibrillator. Nor is he the only one not doing so well. One of his ex-wives has a stroke.

Another character, having already lost her husband to brain cancer, commits suicide after her back pain becomes too much to bear. "Old age isn't a battle," the protagonist thinks to himself after calling a former colleague who is dying in a hospice. "Old age is a massacre."

"This book came out of what was all around me, which was something I never expected — that my friends would die," Mr. Roth said. "If you're lucky, your grandparents will die when you're, say, in college. Mine died when I was a schoolboy. If you're lucky, your parents will live until you're somewhere in your 50's; if you're very lucky, into your 60's. You won't ever die, and your children, certainly, will never die before you. That's the deal, that's the contract. But in this contract nothing is written about your friends, so when they start dying, it's a gigantic shock."

There was a long, melancholy stretch, Mr. Roth said, when it seemed he was attending a memorial service every six months or so, and it culminated a year ago with the death of Saul Bellow, with whom he had grown particularly close in the years after Bellow left Chicago and moved to Boston, closer to Mr. Roth's home in Connecticut. "It should have dawned on me that Saul was going to die," he said. "He was 89, I think, when he died. Yet his death was very hard to accept, and I began to write this book the day after his burial. It's not about him — it has nothing to do with him — but I'd just come from a cemetery, and that got me going."

Mr. Roth added that when he began thinking of novels about death and illness — not just books in which sick people die, but those that take illness as their main subject — he couldn't come up with many beyond the obvious: Mann's "Magic Mountain," Solzhenitsyn's "Cancer Ward" and Tolstoy's "Death of Ivan Ilyich."

"Many great books treated adultery," he said, "but very few have treated disease. So I thought to make this man's biography his medical history — just make the medical history the narrative line — and see what happened."

The title "Everyman," which is an allusion to the medieval morality play, was not exactly an afterthought, Mr. Roth said; more nearly a halfway thought. "I think I went all the way through the first draft without realizing the character didn't have a name," he explained, "and then it struck me as useful to deliberately keep it out." As soon as the Everyman connection occurred to him, Mr. Roth took down the "Survey of Western Literature" text he used in his freshman year at Bucknell and reread the play, in which a nameless figure is called to account for his life, for the first time in years.

"It was hair-raising," he said. "All the terror that's in it. It's told from the Christian perspective, which I don't share; it's an allegory, a genre I find unpalatable; it's didactic in tone, which I can't stand. Nonetheless there's a simplicity of approach and directness of language that is very powerful."

In a passage early on, Everyman meets a messenger and says something like, You're not a messenger, and the messenger allows that he is indeed Death. Everyman is startled. He says, 'Oh Death, thou comest when I had thee least in mind.' The line just knocked me for a loop."

Not all the research was so gloomy. The father of the novel's protagonist is the owner of a jewelry shop, and Mr. Roth, who as a student worked briefly in the jewelry department of the old Bamberger's in Newark, said he enjoyed teaching himself about clocks and watches. "I was never in business, but I certainly get a kick out of writing about business," he added. He even made a field trip to a jewelry story, but not to the 47th Street diamond district, he said, because "I figured they'd just say, 'Do you want to buy or not?' "

Instead he walked north on Broadway until he found a shop run by a Dominican who didn't mind talking to him. Mr. Roth was prepared to pretend he was buying an engagement ring and even had $500 in his pocket he was ready to spend, but in the end it proved unnecessary. "I got off scot-free," he said.

Mr. Roth declined to talk about what he was working on now except to say that he thought it would be about the same length as "Everyman." He explained: "The thing about this length that I've particularly come to like is that you can get the impact of a novel, which arises from its complexity and the thoroughness of detail, but you can also get the impact you get from a short story, because a good reader can keep the whole thing in mind. Motifs can be repeated, and they will be remembered."

He paused and added: "You know, I used to talk this way about the pleasure of writing long novels. If I go into the plumbing business next week, I suppose I'll be talking this way about toilets."